Dearest Friend,

Grief is often looked at as being this sort of uncomfortable, albeit, compartmentalized process in which those of us people in the Western World have no fundamental understanding about.

The English language itself may in fact be the culprit of all first-world fallacy. It’s like the core principality of our Language is found within its structural accessibility, and yet we forget that this too comes at a cost.

Divisiveness can then be uprooted and withheld by all those who control the Authority of Voice. When the Voice is threatened, more divisiveness begets uprooting, so on and so forth.

Language is both our ladder and our cage. We think we climb toward heaven with it, but we forget that the rungs are carved by hands that may not wish us to ascend at all. English in particular — imperial tongue, convenient code of commerce — has become a tool for efficiency, not revelation. A system meant to categorize, pin down, reduce the living fluid of experience into manageable packets.

So grief, in this context, cannot be understood. Because grief refuses to be managed. Grief is the swelling ocean that defies grammar. It is a sob that spills over punctuation marks. It is the tremor in the hand when the pen falters, and in that faltering, a truth far older than syntax breaks through.

Yet in English we are taught to say the right thing. Offer condolences. Package sorrow neatly so the listener isn’t made uncomfortable. The words themselves betray us — “sorry for your loss” as if grief were only about losing, not also about the wild, unbearable presence of love still thundering in the chest after the beloved has gone.

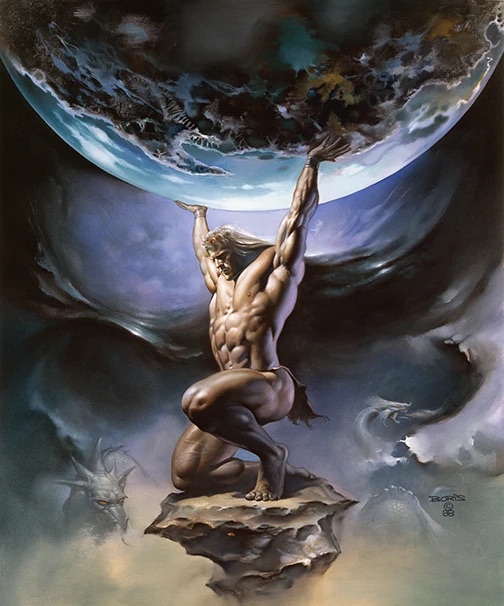

What if grief is not a process but a furnace? Not stages but transmutations. The West likes diagrams: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Convenient bullet points. But no soul has ever moved so linearly.

Grief eats the chart. It devours categories. It burns with an alchemical fire, reducing us into ash so that some other metal might emerge.

Here, grief is ouroboric. It coils around itself, swallowing yesterday’s tears only to produce tomorrow’s salt. It is recursive, a spiral staircase in the dark, where each step upward is also a step downward into memory.

And yet, from this repetition, something else is born. A new alloy of self. A new consciousness. Grief is the forge by which the psyche is tested, purified, or sometimes shattered.

Those who hold the Authority of Voice — governments, churches, media, even the quiet etiquette of family — dictate not only how we grieve but whether grief is permitted at all.

Think of how grief is publicly policed. Cry too loudly at a funeral, and you are whispered about. Fail to cry at all, and you are whispered about differently. Entire cultures of silence bloom from this repression. Men taught not to weep, women taught to weep in ways that don’t inconvenience. Children rushed through their sorrow because it disrupts productivity.

And then there is political grief — who is allowed to mourn publicly, whose deaths become national tragedies, and whose vanish into footnotes. Authority decides which grief matters. Which grief can be televised. Which grief can be sanctified with memorials, and which grief must rot in private corners of the heart.

Thus grief becomes an act of rebellion. To weep fully, shamelessly, is to resist the cage. To write grief without flattening it into marketable language is to reclaim a piece of the soul from the empire of English efficiency.

A tear is more honest than a sentence. It does not translate. It falls in whatever grammar the body demands.

And yet even here, language tries to intrude. We say “crying is weakness,” or “crying is healing.” We assign it roles, functions, purposes. But a tear needs no justification. It is ontology itself — being made liquid.

The tear carries within it the entire paradox of grief: presence and absence fused. Saltwater pulled from a body remembering that it is mostly ocean. The dead live in the tear not as ghosts but as minerals, dissolved into the fluid of the living.

Thus every tear is communion. To cry is to be both alone and together, body and memory and cosmos meeting in the brief shining arc of water on skin.

If English is inadequate, what then? We must move toward a language of gesture, silence, rhythm. Perhaps grief is best conveyed through repetition — like waves hitting shore, not to advance but to insist. Or through music, where tones elongate what words cannot. Or through poetry, which bends English until it almost breaks, forcing cracks through which the inexpressible can leak.

Grief may be the one universal that resists globalization. No empire can fully codify it. No language can domesticate its wilderness. Which is precisely why those in power seek to name, contain, and diagram it. Because grief, left unchecked, can dismantle whole systems. The weeping mother is the first spark of revolution.

-C.