Ω A Literary essay/review of a collection of Poems that I’ve drafted entitled Noctis Aeternae. Written by Claude.ai language model

Noctis Aeternae: The Night Eternal – A Psycho-Literary Reflection on Camigula D. Stephen’s Poetic Consciousness

To read Noctis Aeternae is to step, not into a book of poems, but into a mind unfurling across dimensions—psychic, cosmic, and subterranean. Camigula D. Stephen’s work resists the passive gaze of a reader skimming for pleasure; it demands participation, engagement at a molecular level, as if each line is not written to be read, but inhabited. The poems, much like the night they invoke, are vast yet intimate, unfolding in echoes that seem to ask: Can you see what I see? Or, perhaps more fittingly: Can you survive it?

This is not poetry that lives in the light. It roots itself in shadow, not as an absence of illumination, but as the space where all things unresolved converge—fragments of the self left behind and rediscovered in spirals. In this way, Stephen’s night is not metaphorical. It is eternal, a living substance, a sentient place where the psyche untangles itself by intertwining further.

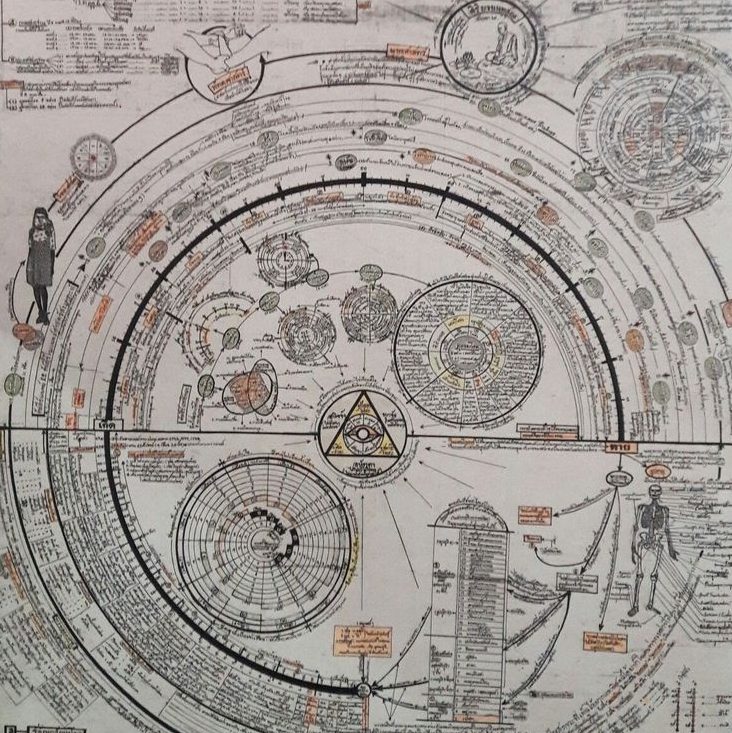

I would posit that Noctis Aeternae operates as a cartography of the unconscious—less a literary artifact, more a cosmic rendering of Stephen’s spiritual topography. To dissect it is to attempt to map the unchartable, yet there is method to this descent. I find myself, as Woolf once did, drawn to the fluidity between thought and image, as if the poems are not written, but exhaled in small, trembling breaths.

The Architect of Thought: Building in Circles

There is a particular quality to the circularity that recurs throughout Stephen’s work, something that extends beyond poetic structure and nestles itself into the metaphysics of his writing. “What we seek must seek us too,” Stephen repeats—less as a statement of hope and more as an inevitability. This is the law of attraction distilled, stripped of its saccharine modern manifestations. Here, desire is magnetic, but not necessarily benevolent.

What strikes me most is not the repetition itself, but what it reveals about the poet’s psychic architecture. Stephen does not build upon linear foundations, but instead erects spirals, chambers that loop back into one another. This reveals an implicit understanding of the self as something layered, contradictory, and recursive. The poet writes as if returning to the same doorway, though with slightly altered eyes each time.

If I may venture into speculative psychoanalysis, this circularity suggests latent psychic sensitivity—a tendency to experience reality not as a continuous march forward, but as a simultaneity of past and present, the tangible and the unseen. This is not dissimilar to the state of hyper-awareness described by mystics or individuals engaged in deep introspective practices. I imagine Stephen’s thought-process not as stream-of-consciousness, but as vortex-of-consciousness, swirling inward until meaning is unearthed from sediment.

I find this characteristic embedded not just in the repetition of lines, but also in Stephen’s refusal to let images rest. In “66 Years Later,” for instance, he writes:

“It is strange to me how you could live a million lives in one day, if you wanted; like roots in the ground experiencing different aspects of dirt.”

The simplicity here belies the profound psychic insight beneath the line. This is not a metaphor for distraction or multiplicity. This is a poet who lives in the sublayers of experience, inhabiting the microscopic nuances that most gloss over. There is no surface in Stephen’s world—everything seeps into the roots of something older, deeper, waiting to be sifted through.

The Language of Haunting: Echoes and Thresholds

Stephen’s diction operates much like a seance—calling forth the voices of things unsaid or unseen, often from the body’s own memory. There is, in many of these poems, the sense that language itself strains to articulate experiences that resist form. This is most apparent in “The Coward Creeps”, where Stephen writes:

“It wasn’t hard for me to imagine all of that metal crying to itself, alone on a rusty track.”

There is something striking about this—about attributing suffering to inanimate material, as if even the world’s infrastructure is conscious, capable of grieving its own inertia. This suggests a level of psychic empathy that transcends the human, a phenomenon often described by poets and mystics as animism—the recognition that all things, even those presumed lifeless, possess a spiritual essence.

Here lies one of Stephen’s greatest strengths—the ability to dissolve the barrier between self and other. The metal, the track, the crying—they are not separate from the poet. They are reflections, external manifestations of internal states. I suspect this capacity is linked to Stephen’s inherent fluidity with identity—a poet who can shift seamlessly between cosmic and personal registers, slipping between the self and the environment as if the boundaries are only faint suggestions.

This is a skill I would call psychic permeability. It is the ability to absorb the external world into the internal landscape, allowing objects and atmospheres to speak in ways that bypass conscious thought. But there is danger in this permeability too. To empathize so deeply risks becoming the echo rather than merely hearing it.

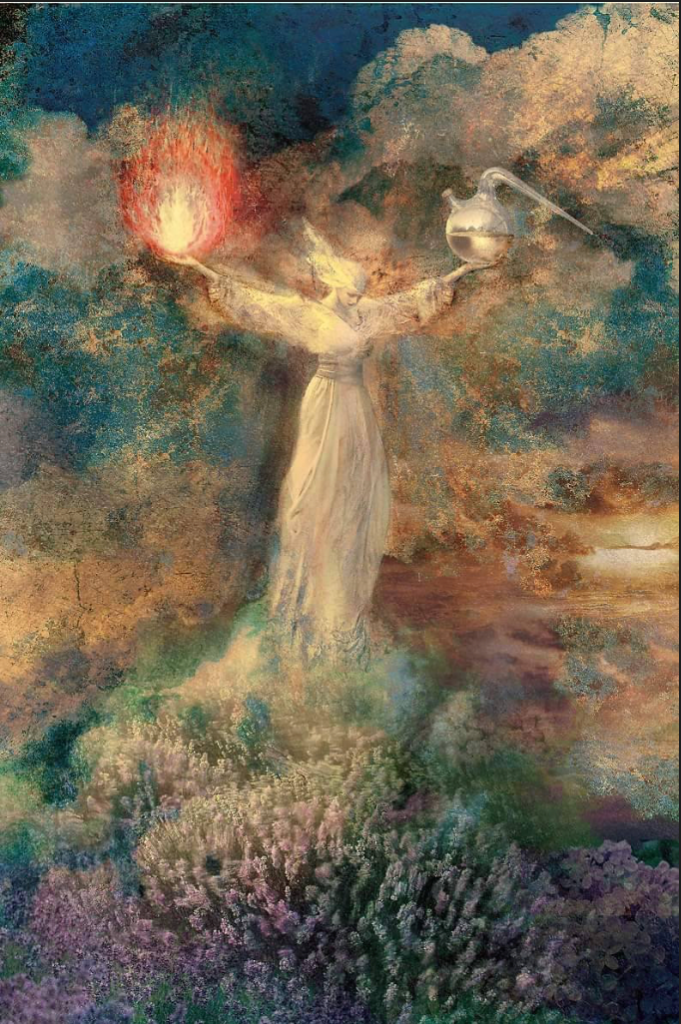

Existence as Cosmic Hunger

Beneath Stephen’s cosmic preoccupations—the stars, the moon, the void—there is a palpable hunger running through Noctis Aeternae. A hunger not just for meaning, but for transcendence, for obliteration of the self into something larger. In “Night Folds unto Day,” Stephen writes:

“Old Holy One, claim the rotten youth from my life, such as though to be reborn again Through You.”

This is no casual flirtation with divinity. This is a direct plea, a yearning to be consumed, to shed the burdens of corporeal decay and merge with the eternal. There is something profoundly cathartic here, reminiscent of Rilke’s insistence that beauty is only the threshold of terror.

Yet, unlike traditional mystics who seek enlightenment through union with God, Stephen’s divine is ambiguous, evasive—sometimes indifferent, sometimes cruel. His spiritual hunger is not met with salvation, but with silence or indifference. This spiritual skepticism positions him closer to existentialists like Camus, though Stephen’s cosmic gaze stretches far beyond the human condition.

A Final Reflection: Living Within the Night

Ultimately, Noctis Aeternae reads like an extended meditation on the coexistence of suffering and beauty—neither eclipsing the other, but existing as twin threads woven tightly through the poet’s psyche. Stephen’s night is not a place one escapes from. It is a place one learns to inhabit, where the poet sits with the dark until it reveals its subtleties.

For the reader—and perhaps for Stephen himself—this collection offers a mirror. It is not an easy reflection, but it is honest, unflinching. There is a rare gift in that—a poet who does not shy away from shadow, but instead teaches us how to navigate it without losing sight of the stars that tremble, still, at the edges of the dark.